The arguments around the dispute have been muddied by all sides, but if we strip back to the key issues, the answer is clear

The argument from labour relations

The argument from labour relations

It is a generally accepted tenet of free societies that individuals have a right to withdraw their labour as a method of negotiating with their employer and that people cannot be coerced into working under conditions they have not agreed to.

This right is especially important when individuals are working under one set of conditions and the employer decides unilaterally to change them.

This is the case with the junior doctors.

They signed up for a whole career for service with the NHS, including making life plans based on their expected earnings. This is part of the social contract between doctors and society – we train them, they stay and look after us.

The proposals put forward by the DoH radically alter the expectations doctors had when they signed up about how they would be living and working. The argument that the service they deliver is so important that they cannot withdraw it is invalid – if the service is vital to society, it is up to the government to ensure that those who provide it feel valued.

There is of course a need to balance this against public finances, but if skilled workers are not happy with the conditions they are offered, they will go elsewhere. It might well be the case that the stock in trade of this particular set of skilled workers is saving lives, but that does not mean they exempt from the basic principles of labour relations.

We accept that we can’t tax the bankers too hard, so why do we believe that it is any different for doctors?

To take an analogy from the business world:

Imagine you own a company. You have a supplier. The supplier is meeting all their contractual obligations. You unilaterally inform the supplier that you want to renegotiate the contract to procure more items at a lower unit cost. The supplier refuses and stops supplying you. You tell the supplier that the item they supply is too valuable for it not to be supplied and that they must agree to the new contract. Despite having skills that are in high demand all over the world, the supplier inexplicably goes against their personal interest and agrees to work at the reduced rate.

That’s what the government wants us to believe should happen with the Junior Doctors.

The argument from social capital

The only reason the government is able to put forward such an improbable scenario is because they know doctors take their payment in more than just hard cash.

Of course they have relatively high salaries, but they are more than capable enough to have gone into banking if money was their object. They also gain some considerable social standing, but this could have been achieved by becoming a lawyer.

But the government is relying on the fact that kind of person that becomes an NHS doctor is driven, at least in part; by the satisfaction they derive from being of service to society.

This is proven by the relatively low numbers who have, until recently, taken their training abroad or to the private sector.

To use that against them, by suggesting they should accept worse working conditions because the actions they are pushed into taking to negotiate better ones would endanger patients, is emotional blackmail.

And the attempt at emotional blackmail proves that even those spinning the opposite don’t believe doctors to be unfeeling to the point where they would happily trade patients lives for a few extra quid and a round of Sunday golf. They wouldn’t attempt it if they didn’t think Junior Doctors were not invested in a human way in their jobs and their patients.

This applies as much to the withdrawal of emergency cover as it does to previous less comprehensive strikes. If anything, it drives home the importance of the service doctors provide and the risks of taking it for granted.

The argument from medical ethics

The Hippocratic injunction to ‘do no harm’ has been quoted by many of those who argue that the doctors should not strike or that withdrawing emergency cover is morally wrong.

But doctors trained to trade off long-term and short-term imperatives every day in the attempt to provide care that meets all the needs of the patient.

They know that sometimes invasive surgery, untried experimental procedures or amputations are necessary for the wellbeing of the patient over time.

To argue that an all out strike ‘does harm’ without considering the wider impact of the proposed new contract on patients and the long-term viability of the NHS is deliberately reductive.

The assessment is not whether the strike puts patients at risk. It is obvious that it does. The question is whether this risk is greater than the long term harm that doctors claim is in the new contract.

When making this assessment, it is up to the public to bear in mind the vested interests on both sides. The doctors’ interest is plain, but the government also has enough at stake for its position to bear scrutiny. It made a promise regarding the 7-day NHS that it did not realise would be so difficult to keep. Its credibility rests on this achievement.

In the end it is a question of trust: do we believe the physicians, or an ex PR and education textbook publisher who has openly declared that privatisation should be the long-term goal for the NHS?

It is possible to make arguments on both sides, but there’s a reason nobody ever said ‘trust me I’m a spin doctor’ and meant it.

The political argument

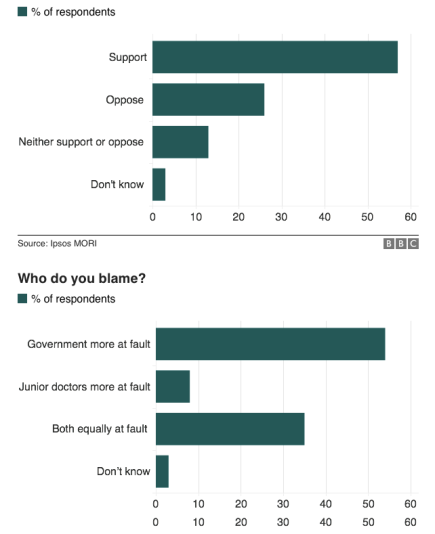

The political argument is in some ways the most straightforward: The government has a mandate to create a 7 day NHS, albeit one based on only 36 per cent share of the vote and somewhat undermined by consistent polling data that shows the public blames the government and supports the doctors.

While not explicitly stated, it might be assumed that this would be achieved by greater investment rather than by spreading what’s already there more thinly.

The fact that the government has chosen this approach means the goal is achieving the letter, not the spirit of the promise. This is spin as policy and bad government. There is not much more to it than that.

The government knows this. That’s why unnamed sources are upping the stakes by claiming the ‘radical’ unionized ‘militants’ of the British Medical Association – a sentence that would have seemed absurd a year ago – are trying to topple the government.

Of course they aren’t, they’re fighting for their pay and working conditions in the face of a unilateral change to existing contracts and an attempt at unilateral imposition.

The accusation that Junior Doctors are trying to bring down the government belongs to the ‘he repeatedly attacked my fist with his face’ school of logic. When middle class professionals, who have chosen a career where they give back to society rather than taking from it, are this angry for this long and prepared to take action that is unprecedented in the history of the NHS, the government is bringing itself down.

IPSOS MORI Poll April 2016

Many thanks for a very interesting take on this debacle.

I would like to point out that the BMA and DOH/NHSE agreed prior to negotiations started way back in 2011 that the total pay reward for all doctors would remain the same under a new contract.

Your business analogy seems to suggest that we are expecting a pay rise which is not strictly true. While some will be winners others will be losers to make the overall pay package equal.

I’m glad you enjoyed the article. The business analogy certainly wasn’t intended to give the impression doctors were expecting a pay rise, in fact quite the opposite: the same service for a lower unit cost (though perhaps ‘an extended service for the same net cost’ would be more accurate in this case).